This post got a bit longer than my standard bite size semiotic posts, so let's call this a snack size post.

I've been reading through an interesting article by Chesnut et al about "Multilingual Commanding Urgency". I won't even try to give the full article and its results a proper summary (you should just go read it), but in short it is a good take on how the authorities behind directive signs might be choosing which languages to use - and how the results can be stigmatizing for specific language user groups.

I've been known to be interested in multilingual aspects of signs before, and the article by Chesnut et al was something that a few different linguists I know have recommended to me when I've mentioned interests in the nuances of multilingual signs. Now that I finally took time to read it, I can see why. (It's very good.)

Now. In Chesnut et al the focus is on situations where the underlying theme is that of directive signs1 that aim to restrict behavior by e.g. ordering how to handle trash or to use masks. The use of different languages is seen to mirror the sign posters' beliefs on which language using groups are more or less likely to take part in unwanted behavior, and the aim of the addition of languages is to lessen the burden on enforcing the desired behavior. To quote the article for a proper definition, they define Multilingual Commanding Urgency as follows:

Multilingual commanding urgency is the impetus to make directive signage multilingual due to the belief, not necessarily based upon actual practices, that one or more differently speaking language communities is likely to not comply with a stated directive, and an understanding that successful communication regarding relevant directives will reduce the enforcement burden of authorities.

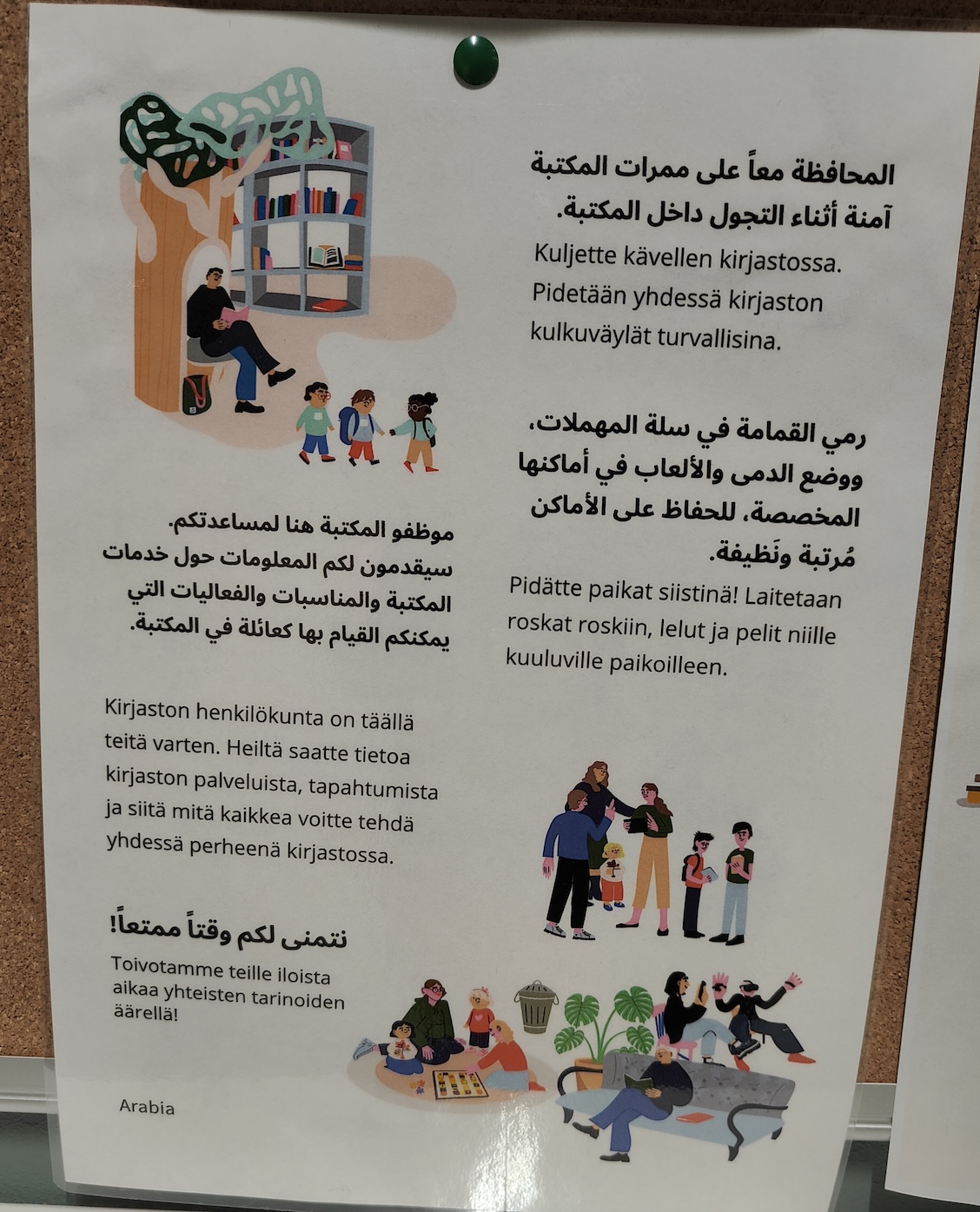

This all brought to my mind the following sign I saw a few weeks ago in a public library in Espoo, where besides all the book-related stuff the aim of the library is to provide a sort of communal living room for the inhabitants of the area.

The sign, a laminated A4 which has been probably produced in-house, lists various guidelines in Arabic and Finnish. A crucial thing to note here that Finland is bilingual, with Finnish and Swedish as the two official languages while English tends to be the lingua franca, especially in signs, for speakers of "all the rest" languages. At least in 2021 Arabic ranked as the fifth most common language with less than 1% of speakers. So this sign using only Finnish and Arabic is a message in itself. Especially as the Arabic is listed first.

I've translated the Finnish versions quite literally below, the emphases being from me:

- You should move by walking. Together we can keep the walkways safe.

- You keep the place clean! Let's2 put the trash to trashcans, toys and games in to their proper places.

- The library staff is here for you. From them you can get information on library services, events and on everything you can do in the library together as a family.

- We wish you happy times with shared stories.

So the Finnish version uses very polite language. The viewer is referred to with the Finnish "polite plural you" when giving out rules in 1&2, and that rule-giving is further softened by a second sentence explaining a reason for the rule, and describing how we will be working together to achieve our goals. Furthermore, the third and fourth points soften the message even more by describing how this place welcomes the reader and their family to enjoy it.

I don't read Arabic at all, and so I am at the mercy of translation systems until I have time to bug someone who does. But according to the GPT-o3 the Arabic version uses similar styles of polite address as the Finnish text. Another thing that pops out to me here is that the Finnish text is not wrong, but some things are stated in a bit peculiar manner. The o3-powered analysis is not conclusive3, but it seems that the Arabic version is completely fluent, and the Finnish version might be written with the extra aim of assisting Arabic speaking people to learn Finnish by having a somewhat literal translation?

Also from the design point of view, I note that I would have kept the first two text boxes to the left of the page and the image on the right. I am getting a vibe that this organization of visual and textual elements also reflects the right-to-left direction of Arabic script. I'm guessing the whole poster was designed and written by a native Arabic speaker, which further increases the feelings of inclusivity.4

And this all brings me to the "Multilingual Welcoming Urgency" part in the title of this post. Here we seem to have a sign that, while giving out some directive or restrictive orders, is mainly focusing on welcoming people speaking a specific language. The choice of language is still driven by the beliefs of "the authorities" on which language speaking groups would be most in need of the information conveyed by the signage. But the underlying motivation is not on reducing the enforcement burden at all, almost the opposite. Indeed, in total this sign looks to me like some sort of semiotic antonym of the signs described by Chesnut et al. Which made it a refreshing contrast point while reading their work.

To conclude, I want to emphasize that I don't think this is the most natural approach to analyzing this sign. A more natural approach would be to base the reading to some groundwork on inclusivity via multilingualism, which I assume to be a full field of its own.5 And this post would probably benefit a great deal from even a cursory read of Nishiyama. But this is not an academical journal, this is me enjoying myself in the world of semiotics. And the experience of reading a paper with a polar opposite example as a contrast in mind is something I would recommend to everyone, and something I'll hope to be able to repeat with as many papers as possible in the future.

P.S. There is also an interesting analysis to be made on the choice of visual components, but for the sake of brevity I'll leave that as an exercise to the reader, with a suggestion to first read Schimkowsky. I advise to pay special attention on how they discuss the 'offer' vs 'demand' aspect of images, and the choice of point of view for the sign observer. Then come back and look the images here.

-

I.e. signs that are directing you to follow some orders, like "No loitering" or "Curb after your dog". ↩

-

The Finnish plural conjugation is used here, referring to "we". ↩

-

I really need to bug someone who speaks fluent Arabic. ↩

-

The sign does read "Arabia" ("Arabic" in Finnish) in the lower left corner. Indexing a specific language here implies that similar signs have been produced in other languages as well, which further hints at a more coordinated effort. I guess I'll have to go and ask them as I visit the library quite often. ↩

-

A cursory search suggests terms like "linguistic inclusion in the public space", "linguistic landscaping for integration" or "top-down language accommodation". ↩